By Maya Bouchebl

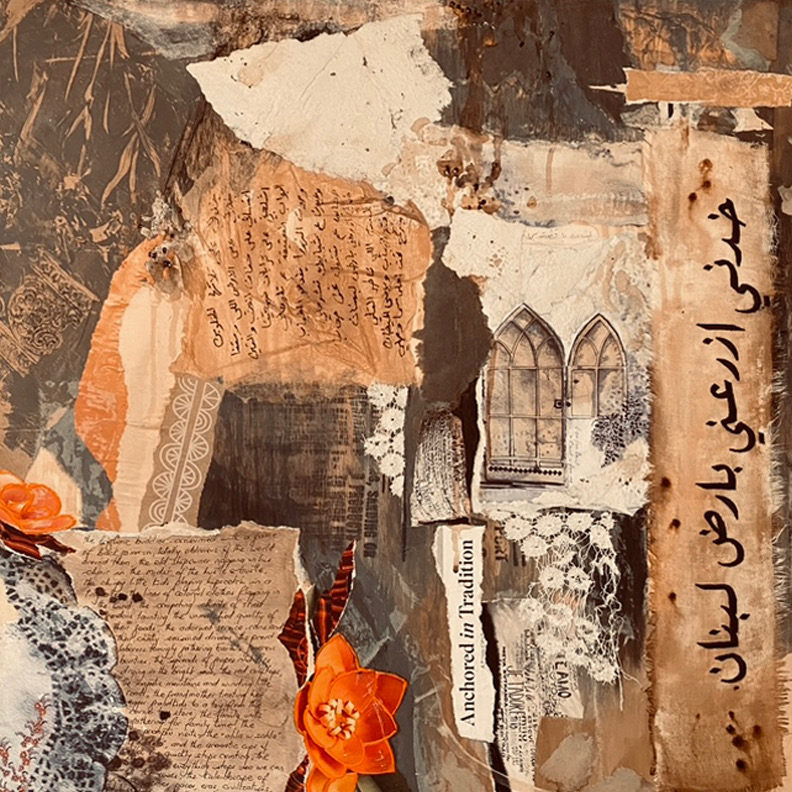

The first wave of Lebanese immigrants came to the United States in the late nineteenth century, as thousands of Middle Easterners left their countries due to turmoil in the Ottoman Empire. Today, most people of Lebanese descent live outside of the country, with one of the biggest Lebanese American communities in Houston. One notable member of this community is Dr. Dima Abisaid Suki: a healthcare professional by day and an artist by night. After immigrating from Lebanon to Houston in 1988, she studied epidemiology and worked as a medical researcher at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. She eventually became a professor and director of clinical research and operations for the Department of Neurosurgery. Also an artist and writer, she expresses her immigrant experience through her creative work. Suki shared her story from her childhood in Lebanon to her current life in Houston in a recent interview.

Suki was born in Beirut, the capital of Lebanon, in the mid-1960s. She had an idyllic early childhood, with many happy memories of playing with her cousins and visiting beautiful landmarks across the country. Life became more difficult, however, when the Lebanese Civil War began in 1975. Many readers may be unfamiliar with the history of this conflict, especially since the war’s background is so complicated that Lebanese people often avoid trying to explain it. In summary, multiple political factions with militias and foreign allies were engaged in an armed struggle for power over the country for fifteen years, during which residents suffered through poverty and dismal living conditions.

For years, Suki and her family were “confined to small areas of the country [in] fear of being killed or kidnapped by … their own countrymen or foreigners who took part in the war.” Many were caught in the crossfire between the warring factions or subjected to abuse by occupying forces. She went on to describe the notorious military checkpoints: “We used to get stopped and insulted at these checkpoints by all sorts of disgusting people. … [W]e used to consider ourselves lucky that nothing worse happened at those checkpoints, because sometimes people got beaten [and] kidnapped.”

Despite the dangers for all those years, Suki, her peers, and society were expected to carry on as usual. The Lebanese prioritized education so the schools did their best to continue operating. Oftentimes, Suki studied for her exams by candlelight while hiding from bombs in the safest corner of her house. She and her friends were sometimes “under bombs one day and partying the next.” She reflected, “It was very interesting. We took it one day at a time.” They found moments of reprieve that made life bearable. Suki attended the American University of Beirut, receiving her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in nutrition. She traveled throughout Europe, developed lifelong friendships, and fell in love with her future husband. Together, the couple moved to America.

In 1988, the civil war was only two years away from its conclusion, although it did not seem like it at the time. Suki and her then-fiancé both wanted to continue their education, but the American University of Beirut had suspended its PhD programs. Like many others at the time, they decided that moving to a different country offered their best option to achieve their goals. The couple believed Houston was the ideal place to begin their lives together, as they both had their eyes on the University of Texas (UT) School of Public Health, and Suki’s fiancé already had several relatives living in the city.

The path forward was clear, but the process of moving to America felt daunting. The American embassy in Lebanon was closed, so visa applicants had to take potentially dangerous trips to the embassy in Damascus, Syria, instead. Suki and her mother took a taxi to the embassy and arrived before sunrise, only to find a long line of Lebanese citizens already anxiously waiting. Suki worried as she watched most of the applicants leave their interviews looking disappointed. She thought about the “lifetime[’s] worth of hopes and dreams” she planned with her future husband, all hanging in the balance of one stamp on a passport. The agent gave a once-over of her acceptance letter from UT School of Public Health, stamped her passport, then said, “Good luck in America.” Suki joined her fiancé in Houston where they pursued public health education and careers, and, as the years progressed, they became American citizens.

To read the full story, click on Buy Magazines above to purchase a print copy or subscribe.

Follow

Follow