By Megan R. Dagnall

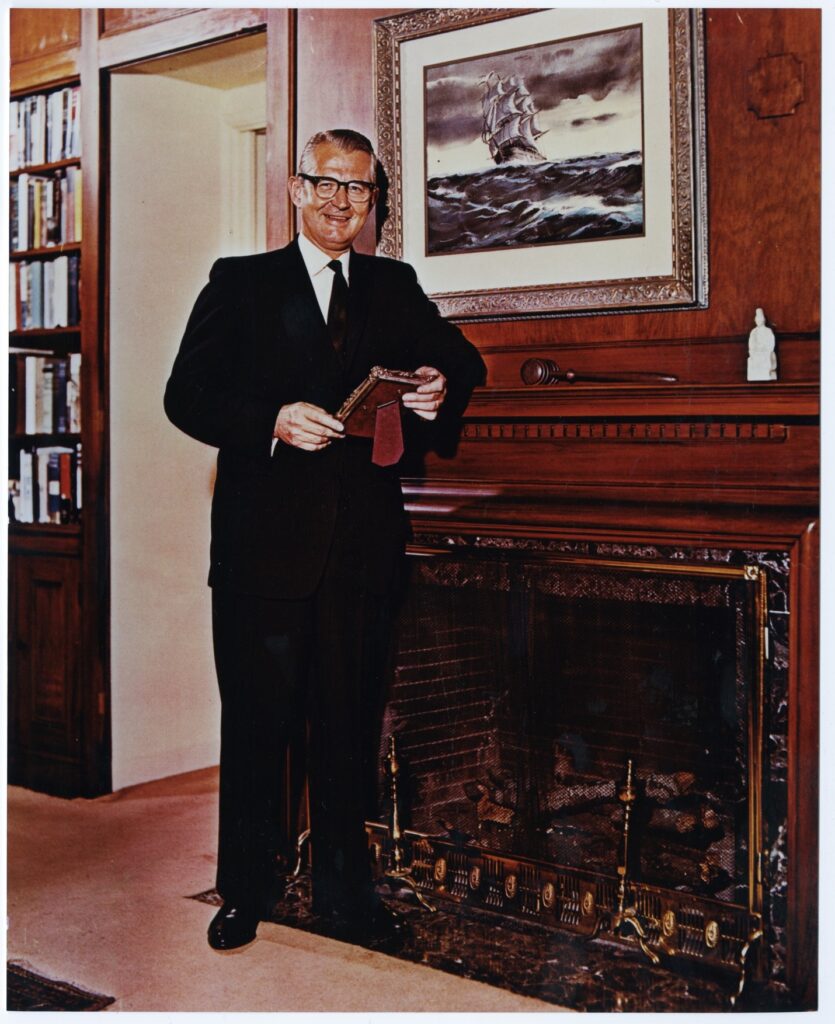

As one of the most ethnically diverse major research university in the United States, the University of Houston’s identity is intertwined with its varied, multicultural student body. With students from 137 different nations, the University of Houston (UH) is a melting pot of cultures and identities that reflect the city’s community. Knowing that makes it hard to imagine that UH was an all-white institution until it admitted its first Black students in 1962. The university’s leadership has made significant progress in the past sixty years to become a more progressive and inclusive institution committed to the value of diversity, equity, and inclusion, beginning with former president Philip G. Hoffman. As the fifth president of UH and first chancellor of the University of Houston System, Hoffman obtained state support, expanded enrollment and facilities, created the University of Houston System (UHS), and opened the University of Houston to Black students. Known as the builder of modern UH, Hoffman initiated the processes that not only desegregated UH but also moved toward integrating it by making the campus a safe and accepting space for students and faculty of all backgrounds.

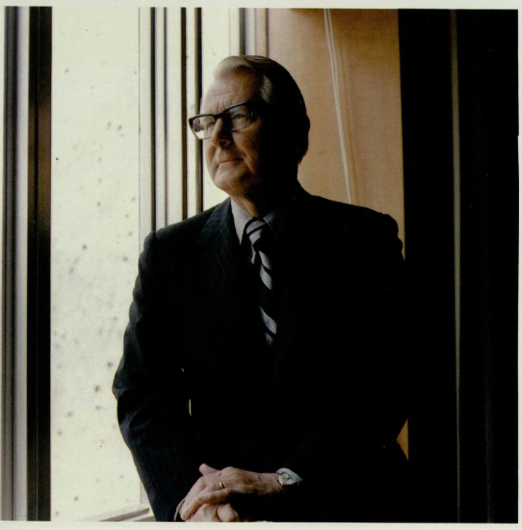

Philip Hoffman was born on August 6, 1915, in Kobe, Japan, to missionaries Benjamin Philip Hoffman and Florence Guthrie Hoffman. When Hoffman was five, the family moved to Oregon. He graduated with a business degree from Pacific Union College in 1938 and a master’s degree in history from the University of Southern California in 1942. After serving his country in the Navy as an intelligence officer during World War II, Hoffman earned a doctorate in history at Ohio State University, where he lectured from 1948 until 1949. He subsequently taught at the University of Alabama, Oregon State System of Higher Education, and Oregon State University. In 1957, Hoffman came to the University of Houston as vice president, dean of faculties, and a history professor. When he began his tenure as president of UH in 1961, it was a segregated private institution facing financial troubles.

In 1927 at the request of working students who wanted to further their education, Houston Independent School District (HISD) founded two segregated institutions, Houston Colored Junior College for African American students and Houston Junior College for white students. Both met in local high schools and transitioned to four-year institutions in 1934, becoming the Houston College for Negroes (now Texas Southern University, TSU) and the University of Houston. Like most higher education institutions in the Jim Crow South, UH did not accept African Americans based on the Supreme Court’s “separate but equal” ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896).

In 1935, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) began challenging segregation in schools through a culmination of cases taken by the U.S. Supreme Court to challenge the separate but equal doctrine. A critical case emerged from Houston in 1946, when Heman Marion Sweatt, a Black Houstonian, applied to The University of Texas at Austin (UT) law school. No law school in Texas admitted Black students at the time, and UT denied him admission based on his race. Sweatt, with the support of the NAACP, filed a suit against UT and the State of Texas. The Supreme Court heard the case in 1950 and ruled that the UT School of Law must admit Sweatt because the state had no equivalent institutions for Black students. The decision marked an essential step in desegregating higher education, prefiguring the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka ruling in which the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that separate but equal is inherently unequal and began the long process of desegregating public education.

Despite Supreme Court rulings prohibiting segregation in educational institutions, many schools disregarded the decisions with a determination to remain segregated. Public sentiment across the South resisted desegregation as colleges slowly began to welcome non-white applicants. The official conversation around desegregation at UH began on August 31, 1955, when then president Andrew Davis (A. D.) Bruce formed a committee to evaluate admitting Black students. After the three-person panel recommended to continue UH’s discriminatory practices, Bruce formed a more extensive committee about two months later, who advised the administration to desegregate immediately and quietly. Despite the report, UH remained segregated until Bruce resigned, and Hoffman accepted the presidency.

President Hoffman understood the solution to the university’s financial troubles began with state affiliation, which could not be accomplished if the university remained segregated. Discussing desegregation of the university on January 22, 1962, Hoffman remarked, “Effective September 1963, the UH will become a state institution, and at that time it will be mandatory as part of the normal pattern of responsibility to integrate.” Hoffman, eager to desegregate, did not want to wait that long, saying, “I have been thinking a little bit about our voluntary and privately moving toward this integration without waiting until we are forced to do it legally… and thus proceed by slightly more than a year before we have to integrate.”

To read the full article, click here, or click on Buy Magazines above to order a print copy.

To read the full article, click here, or click on Buy Magazines above to order a print copy.

Follow

Follow