By Emily Harris

The soul of Houston has been shaped by the journeys of its people. One of the most ethnically diverse large cities in the United States, Houston reflects a mosaic of experiences from people all over the world. The path to this distinction began at the onset of the twentieth century, as the migrations of three key ethnic groups transformed the character of Houston: black Texans, Creoles of color, and ethnic Mexicans. This movement of peoples changed the city’s culture as much as its demographics, as individuals brought their histories, traditions, and identities with them.

Musical styles are intrinsically linked to the passage of such qualities from ancestral lands to new environments. The sounds accompanying migrants and then recreated in Houston became sonic markers of space and, with time, produced uniquely local styles reflective of a blended cultural scene. The foundation for Houston’s musical legacy was built upon the traditional regional styles brought by migrants of the early twentieth century, as identified by historian Tyina Steptoe: blues from black East Texans, la-la from Louisiana Creoles of color, and the variety of sounds from the Rio Grande Valley created by ethnic Mexicans, such as corrido, ranchera, and conjunto. Once in Houston, the interaction with urban space, Jim Crow society, and ethnic diversity impacted the composition and performance of these regional sounds. Such artistic responses illustrate promotions of collectivity among migrant communities. The emerging presence of regional musical styles in Houston demonstrates migrants’ active efforts to preserve their sense of heritage, community, and identity in the place they came to call home.

Black East Texans and the Blues

The sound of blues music is inherently tied to the black experience in the rural Southeast. Landowners in the antebellum South pushed westward to protect the institution of slavery, and this produced an enslaved black population in Texas forced to work on cotton and sugar plantations. African Americans strove to recreate their cultural practices in the counties of eastern Texas, utilizing their limited agency in a profound way. Work songs with themes of lamentable suffering, as well as resilience and deliverance, not only provided individual release but also forged a sense of community for the enslaved in Texas, which derived from their shared experiences of bondage.

The blues has its roots in such work songs. As an art form, the blues had allowed rural black southerners to articulate a “collective sensibility in the face of constant attacks by the plantation bloc and its allies.” Steptoe cites writer Ralph Ellison, who identifies songs containing the “blues impulse” being structured around a three-step process: “identifying a source of pain, expressing that painful experience in a ‘near-tragic, near-comic’ voice, and finding affirmation of one’s existence in the process.” Acoustic guitar patterns, AAB-patterned verses, and guttural moans defined East Texas blues. Generations of black musicians who were born free sought to separate their sound from the banjos and fiddles of their parents or grandparents, and instead utilized guitars to achieve a more emotional range to confront the realities of post-Reconstruction freedom. Furthermore, the prevalence of vocalization over enunciation of the lyrics reflects the deep expression of black suffering without allowing the hardship to triumph.

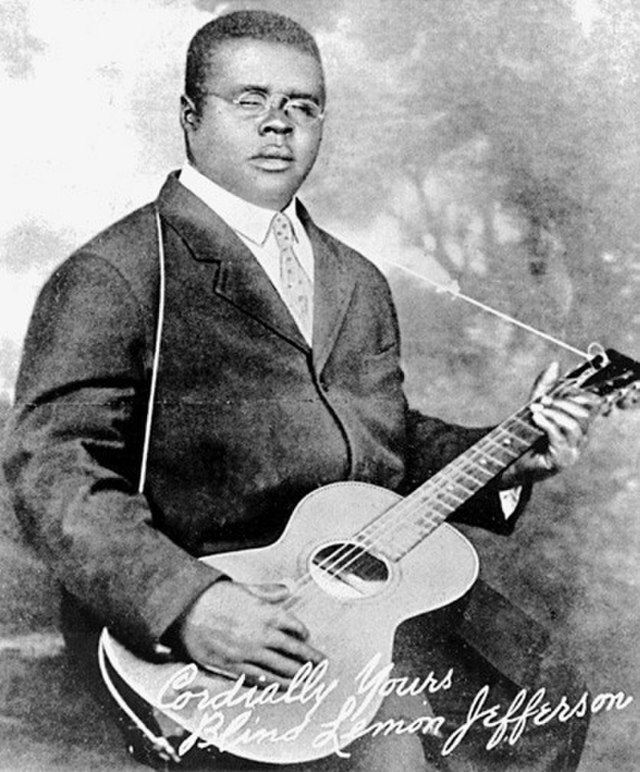

Songs by musician Blind Lemon Jefferson embody the distinct Texas blues sound. Born in Couchman, Texas, in 1893, Jefferson became one of the foremost country blues musicians during the pre-Depression era, epitomizing the bluesman whose lifestyle and songs were filled with despondent imagery. Some of his songs describe the poverty and injustices confronted by black people in the Jim Crow South. One such song, “Prison Cell Blues,” speaks to the criminal justice system. Picking a melody on the guitar, Jefferson wails lyrics which protest the corrupt imprisonment of black people like himself. Other songs such as “Bad Luck Blues” reveal his own struggle to earn a living as an uneducated, blind musician:

I wanna go home and I ain’t got sufficient clothes

Doggone my bad luck soul

Wanna go home and I ain’t got sufficient clothes

I mean sufficient, talkin’ ‘bout clothes

Well, I wanna go home, but I ain’t got sufficient clothes.

Jefferson plays a somber melody while moaning the bitter lyrics that symbolize his longing for security in the face of hardship. Country blues musicians like Jefferson with their faithful guitars traveled around countryside towns and big cities playing for events that catered to working-class audiences. This developed a network of musicians and audiences eager to perform and hear Texas blues as it permeated rural landscapes and urban centers.

To read the full article on the musical influence of African Americans, Creoles of color, and ethnic Mexicans, click on Buy Magazines above to subscribe or order a print copy.

Follow

Follow