By Don Looser

Women have played significant roles in the history of Houston’s cultural development. Some have had talent; some have had resources; some have had influence as powerful journalists or fundraisers. Among these women were Houston’s cultural impresario Edna Saunders and the formidable journalist Wille Hutcheson. Three other remarkable women, however, were historically strategic in shaping Houston’s cultural timeline. They were Emma, Ma, and Johnny.

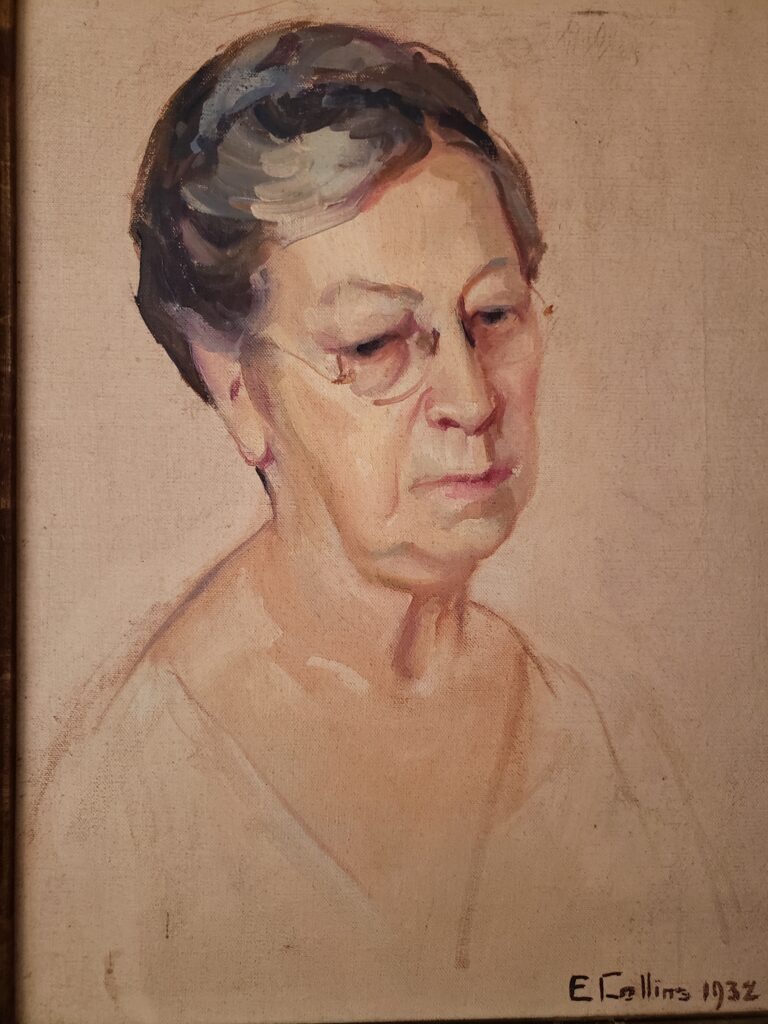

Emma Richardson Cherry

Jane Austen is noted for her literary classic Emma, but Houston had its own renowned Emma, considered founder of the city’s modern art movement. Today, Emma Richardson Cherry may best be remembered for her association with the Nichols-Rice-Cherry House.

Born in 1859 in Aurora, Illinois, Emma and her husband Dillon Brook Cherry moved to Houston in 1896 when Houston’s population was a little over thirty thousand residents. Schooled in New York and Paris, Emma brought to Houston her ties to the world’s finest art. She had studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and was a student of William Merritt Chase. One of Houston’s earliest female artists, Cherry worked in oil, watercolors, pastels, and pencil. Her extensive oeuvre included portraits, still lifes, landscapes, modernist paintings, and historical paintings of Buffalo Bayou. The most accessible of her works today are four large murals completed in 1934 in the Julia Ideson Building of the Houston Public Library.

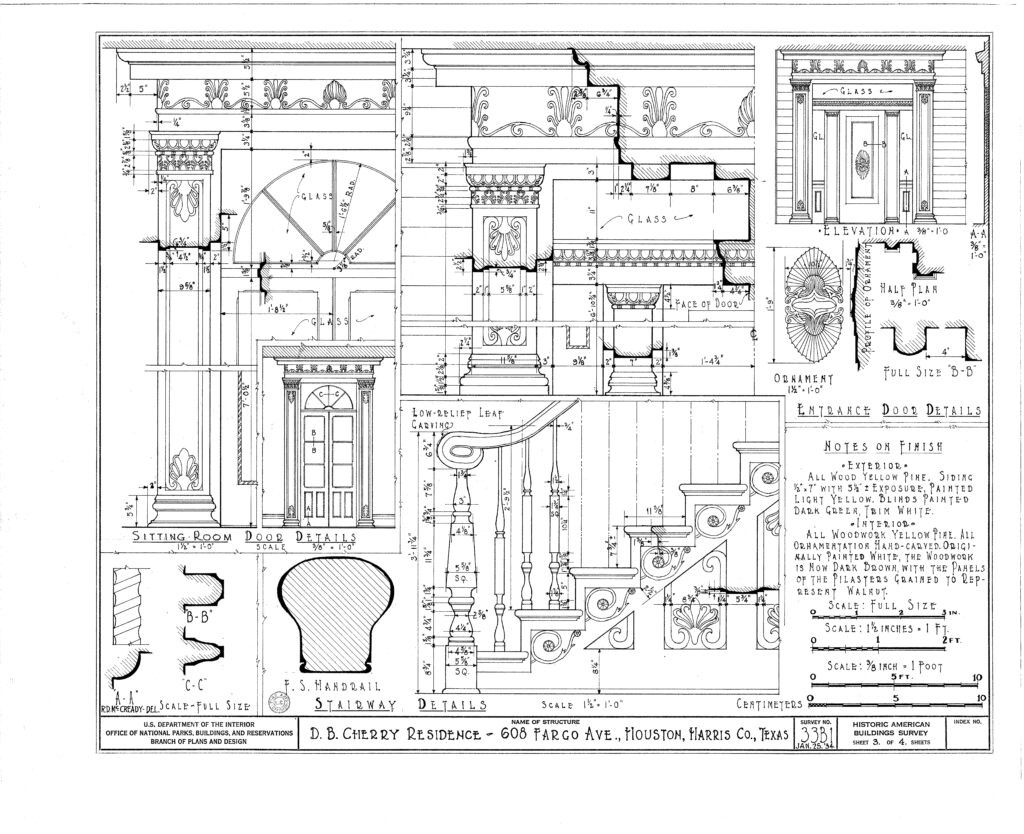

Unexpectedly, Cherry purchased what is today known as the Nichols-Rice-Cherry House, the elegant home of the founder of Rice Institute, William Marsh Rice, which was built in 1850 on the site of the present Harris County Family Law Center. In an auction, Cherry bid $25 for the home’s ornate front door casing and intricate interior millwork. To her surprise, she was the only bidder and acquired the entire house, which belonged to John Finnigan and whose daughter Annette had saved it from demolition. Cherry moved the house to the Montrose area – an operation consuming forty-six nights and costing $450. The Harris County Heritage Society later acquired the house and moved it to Sam Houston Park.

In 1900, Cherry helped organize the Houston Public School Art League that provided schools with reproductions of old master paintings. She often spoke of loading her buggy with reproductions of noted artworks and trotting down Houston’s dusty streets to schools all over town. One gift, however, left the school board, as Betty Chapman described it, “aghast with impropriety.” The board feared that a life-size reproduction of the Venus de Milo given to Houston’s Central High School might corrupt the morals of the students. So, the Houston Lyceum and Carnegie Library accepted the statue that stands today in the Julia Ideson Building.

In 1924, Cherry was the first woman to have a solo exhibit at the new Museum of Fine Arts. Her art has enjoyed retrospective exhibitions by The Heritage Society and the Houston Public Library, which also published a commemorative book of her works. After her husband’s death, Emma continued to paint with the help of a magnifying glass until a few weeks before she died in 1954 at the age of ninety-five.

Houston’s art culture rests on the foundation laid down by Emma Cherry, the “Dean of Houston Artists.” As Houston’s first modern artist, she served for decades as the link between the city and the newest ideas in art. Today, art historians continue to regard her and her work as a significant tie between Houston’s early art history and the contemporary art scene. Without Cherry’s remarkable life-time achievements, Houston likely would not be the art center that it is today. Emma Richardson Cherry left Houston much richer than she found it.

To read the full article that includes stories on Ma Graham and Johnny George, pictured below, click on Buy Magazines above to subscribe or order a print copy.

Follow

Follow