Click here to view the Table of Contents

In addition to the Center for Public History, articles in this issue focus on Quality Hill, Dawson Lunnon Cemetery, Congressman Mickey Leland, the Space Shuttle, Mars Rover Celebration, Graffiti, and architect Donald Barthelme.

Letter from the Editor: 28 ½ Years

By Joe PrattMarty Melosi was the Lone Ranger of public history in our region. Thirty years ago he came to the University of Houston to establish and build the Center for Public History (CPH). I have been his Tonto for 28 ½ of those years. Together with many others, we have built a sturdy outpost of history in a region long neglectful of its past.

“Public history” includes historical research and training for careers outside of writing and teaching academic history. In practice, I have defined it as historical projects that look interesting and fun.

In the early years of CPH, the Tenneco Distinguished Lecture Series was great fun. Tenneco’s endowment provided funds to bring to UH prominent historians such as David McCullough, Robert Caro, and Daniel Yergin. As the fees for such speakers began to outrun his budget, Marty refocused the series on less publicized, but equally valuable, events sponsored by departments on campus.

Tenneco also funded a library endowment that became the financial foundation of the UH Houston History Archives. Recently I had the chance to return the favor by helping a group of retired Tenneco executives write a fond remembrance of the history of what I still consider the best Houston-based company ever. Throughout its history, CPH has organized the funding and researchers to write similar histories of other prominent regional organizations and biographies of Houstonians.

We also have organized conferences on issues important to our region. Three of these—on our region’s environmental history, energy policy in the 1970s, and Houston and other cities as energy capitals—have produced published volumes of essays.

The Tenneco book project highlights a central function of CPH, the training of students to do historical research and writing. Tenneco’s history began when a group of outstanding Ph.D. students conducted research on existing sources for the project. One student then took the topic for his dissertation, and his completed thesis became a point of departure for writing the book.

Outstanding students have always been our ace in the hole. Two clusters of Ph.D.s stand out. In the 1980s and 1990s, an excellent cohort of African American history students arrived at our door. They produced extraordinary research on Jim Crow Houston. Better yet, they filled the seminar room with enthusiasm and shared progress, teaching me as much as I taught them. Another memorable cluster of graduate students came together in the recent past to study energy and environmental history. Again, their sense of common purpose and the importance of their research created an outstanding intellectual climate. CPH is proud to have helped UH established a national reputation for excellence in the fields of African American history and energy/environmental history—and to have generated new knowledge about these issues as they affected the Houston region, broadly defined.

Around the turn of the century, the Houston Public Library announced that it would stop publishing the Houston Review of History and Culture after twenty years. The CPH decided to take on this journal rather than see it die. We created the Houston History Project (HHP) to house the magazine (now Houston History), the UH-Oral History of Houston, and the Houston History Archives. The HHP became the dam used to manage the torrent of regional history pouring out of CPH.

Establishing the HHP has been challenging work. We changed the format, focus, and tone of the magazine to reach a broader audience, which has been easier said than done. Applying for grants was no fun, but reading letters announcing substantial grants from the Houston Endowment and other foundations was pure joy. Finding good students to staff these endeavors while juggling the demands of their graduate programs proved difficult, but when the staff came together, we created a pleasant place where “work” often seemed like play.

For thirteen years HHP has provided useful training and funding for many students. Standout teams of student editors include Jenna Berger and Leigh Cutler, Kim Youngblood and Katie Olivares, and Debbie Harwell, Aimee Bachari, and Natalie Garza. The late Ernesto Valdés is in the HHP Hall of Fame for his work on the oral history and his fun-loving spirit. Always ready to help have been long-term supporters and friends, led by Bill Kellar, Barbara Eaves, Steven Fenberg, Betty Chapman, and Jim Saye. They represent all those who have volunteered for our advisory board.

Our work has made the Houston History magazine the best regional history magazine in the nation. Of special note have been issues on San Jacinto, NASA, the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, UH, and the Houston Ship Channel, along with many memorable articles by authors who loved history more than getting paid. (Visit our website to see back issues and subscribe). Writing for the magazine has allowed me to rediscovery my own voice after decades of writing academic histories. The archives is a testament to the hard work of Terry Tomkins Walsh and to the array of important Houston history topics yet to be done. The oral history project has given me an excuse to interview Ben Love, George Mitchell, Mayor Bill White, Larry Dierker, and many other interesting Houstonians.

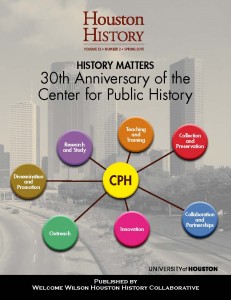

As my career winds down, the Center for Public History dominates my memories of 28 1/2 years at UH. The Houston History Project, recently renamed the Welcome Wilson Houston History Collaborative in recognition of a generous grant by Welcome Wilson, remains central to my work as a historian of the region where I grew up and have spent most of my adulthood. The Center for Public History has created: a vibrant, permanent focal point for research and teaching about the history of our region. Long may it run.

Follow

Follow