By Joe Pratt, Editor

The Houston Ship Channel (HSC) is the economic backbone of the region’s economy, but it is more than that. This path to the sea and the port that has grown to manage its traffic have shaped the region’s “can do” image, given it a national and international identity, and contributed to a distinctively “Houston” culture.

The HSC has been an impressive generator of jobs. The Port’s most recent report in 2012 gives a sense of its far-reaching impacts. It estimates that businesses related to the HSC generate over one million jobs in Texas, producing about $180 billion in statewide economic impacts while generating some $4.5 billion annually in state and local tax revenues. Having grown into one of the nation’s largest ports, the Port of Houston has more than fulfilled the dreams of those who pushed for dredging a channel more than fifty miles long to make Houston an inland deep-water port.

As discussed in the article by Jim Fisher, Houston civic leaders at the turn of the twentieth century convinced the Army Corps of Engineers to dredge the HSC by agreeing to share the costs of the project from the sale of bonds. This “Houston Plan” was, at the time, unprecedented, though it gradually became the national norm. Tom Ball, Jesse Jones, and many other Houstonians pushed through the bond issue for the dredging and then sold the bonds. This episode has gone down in Houston’s lore as a symbol of the “can do” attitude that helped transform Houston from a small regional trade center into a major metropolis. Such boosterism became a defining self-image of Houstonians, who could do and did.

The rapid expansion of the Port’s activities in the 1920s spurred regional growth. The effects were felt not just from the movement of trade in the channel, but also with the expansion of industry along its banks, where large tracts of land became available just as the oil industry boomed in response to the rising demand for internal combustion vehicles. Oil companies needed additional refining capacity, and much of it was built along the HSC, which had a perfect combination of access to deep water and fresh water, abundant natural gas for fuel, large tracts of relatively cheap land, and large supplies of crude oil from the Southwestern U.S., which was then the largest oil producing region in the world. As pipelines stretched from the growing refining complex along the HSC to these major oil fields, the Houston Ship Channel became the hole at the end of the funnel for crude oil from the interior seeking refineries and access to global markets for oil products. Before it was known as an “energy capital,” Houston was known as a major refining center.

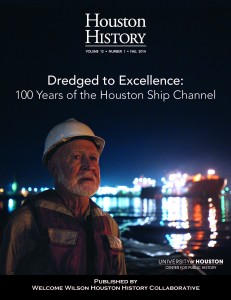

The Port Authority’s article covers the steady growth of trade from the Port of Houston and the expansion of industrial jobs at plants along the HSC. Poor but ambitious workers migrated to these jobs. Their “can do” spirit focused on creating options for their children and grandchildren. The cover of this issue and many of its articles tell some of the stories of the hard working people at the Port of Houston and in businesses along the HSC. An upwardly mobile working class made Houston a city of opportunity. The trade that these workers moved up and down the HSC made Houston an international city.

Articles in earlier issues of our magazine have highlighted broader, less discussed contributions of the HSC and the Port to Houston’s identity and culture. For me, one of the diamonds of our city’s high culture is the John A. and Audrey Jones Beck Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. This spectacular collection of impressionist art was purchased in part by Audrey Jones Beck’s sale of a 6,000-acre ranch along the HSC that she inherited from holdings established by M. T. Jones, her great-grandfather and the uncle of her grandfather, Jesse Jones. The San Jacinto Battleground and Historical Site, the best historical site in the region, holds a special place for me as one of the first outposts of history I ever visited. The elevator at the San Jacinto Monument offers the best view anywhere of the HSC, a view that has fascinated and educated the many visitors I have taken there.

That view brings back memories of a life spent moving back and forth from Beaumont to Houston. Long waits for traffic to clear at the old Baytown Tunnel. The smell as we drove through Pasadena. The massive plates of fried shrimp at the old San Jacinto Inn. The rise of the beautiful Hartman Bridge that replaced the Baytown Tunnel, providing its own views of the construction and operation of the containerization facilities at Barbours Cut and the steady expansion of ExxonMobil’s giant Baytown refinery. Fun trips on the Sam Houston boat tour of the HSC.

The history of personal memory can be disorienting for those who have lived in a region that has changed so rapidly for so long. Events blur and run together. What remains, however, is the reality of the HSC as viewed looking west from the San Jacinto Monument or north from the Bolivar Ferry, reminding us that the HSC and its Port have been defining parts of the history of our region and of our lives.

Articles include:

“Deep Water Houston: From the Laura to the Deep Water Jubilee” by James E. Fisher details the politics and the cultural significance of the push for a deep-water channel in Houston dating back to the first steamship’s arrival at Allen’s Landing in the 1830s to the Deep Water Jubilee that officially opened the Houston Ship Channel in 1914.

“What a Deep-water Channel to Houston Created” by Bill Hensel, communication manager for the Port of Houston Authority, is a centennial retrospective that traces how the Houston Ship Channel and Port of Houston grew to become the world’s largest port in tonnage. It also explores the impact the port has had on the city and how improvements like containerization have revolutionized world trade.

“The Houston Pilots: Guardians of the Waterway” by Debbie Z. Harwell with Sidonie Sturrock looks at the role of pilots who safely guide ships up and down the Houston Ship Channel, the longest inland waterway of its type in the nation. Additionally it details the history of the Houston Pilots organization and the women who have joined its ranks.

“Blue-Water Ships, Brown-Water Bayou: Wartime Construction of the EC-2 ‘Liberty’ Type Cargo Ship at Houston, 1941-1945” by Andrew W. Hall discusses how Houstonians pulled together to build a shipyard in a marshy area along the ship channel and then produced 208 Liberty ships for the war effort, some of them launched in less than two months’ time.

“Working the Houston Ship Channel: Tote that barge! Lift that Bale!” by Debbie Z. Harwell is a photo essay focusing on workers as the backbone of the Houston Ship Channel and Port of Houston.

“The Houston Maritime Museum: The Homeport for Exploring the Maritime World” by Jenny Podoloff traces the museum’s story from its founding by Jim Manzolillo to its current exhibits, which explore maritime history from the Bronze Age to the present, to its future plans to relocate to the Houston Ship Channel. The museum also boasts an exhibit on the history of the Port of Houston.

“Three Continents Studio: From the Bayou to the Biennale” by Jackson Fox explores the development of Buffalo Bayou and the Houston Ship Channel through a study of the waterway by University of Houston architecture students. Their work was recognized at the 2014 Architectural Biennale in Venice.

Follow

Follow