By Adriana Castro

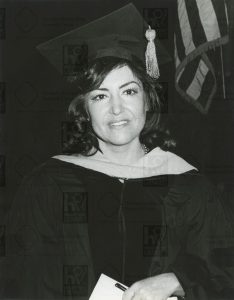

At twelve years old, Guadalupe Quintanilla moved from Mexico to Brownsville, Texas. When her grandmother took her to enroll in school, she was required to take an aptitude test and scored very poorly, so the school classified her as “retarded” or a “slow learner.” The reason she received such a low score had nothing to do with her intelligence; rather it was because the test was administered in English and she only knew Spanish. Quintanilla was placed in the first grade but soon dropped out. Perhaps surprising to some, many years later, this seemingly “slow learner” went on to obtain a doctorate degree, become an administrator and professor at the University of Houston, develop and implement a Cross Cultural Communication Program with the Houston Police Department, receive presidential appointments to the United Nations, and be elected to the Hispanic National Hall of Fame. This is the story of how a first grade drop-out became an outstanding and influential figure in Houston and the United States.

At twelve years old, Guadalupe Quintanilla moved from Mexico to Brownsville, Texas. When her grandmother took her to enroll in school, she was required to take an aptitude test and scored very poorly, so the school classified her as “retarded” or a “slow learner.” The reason she received such a low score had nothing to do with her intelligence; rather it was because the test was administered in English and she only knew Spanish. Quintanilla was placed in the first grade but soon dropped out. Perhaps surprising to some, many years later, this seemingly “slow learner” went on to obtain a doctorate degree, become an administrator and professor at the University of Houston, develop and implement a Cross Cultural Communication Program with the Houston Police Department, receive presidential appointments to the United Nations, and be elected to the Hispanic National Hall of Fame. This is the story of how a first grade drop-out became an outstanding and influential figure in Houston and the United States.

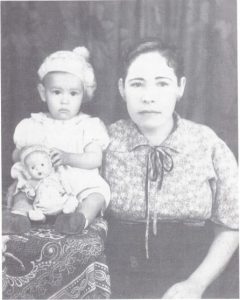

Guadalupe Quintanilla was born Maria Guadalupe Campos on October 25, 1937 in the small town of Ojinaga, Chihuahua, Mexico. She does not remember Ojinaga because, when she was eighteen months old, her parents divorced and she went to live with her grandparents in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico. She recalls, “Living with my grandparents was very nice. Grandma sewed me beautiful clothes and made me dolls from scraps of cloth.” After a few years they moved to San Luis Pedro, Guerrero, to be with her grandparents’ eldest son, Quintanilla’s Uncle Chalio, who had just become a doctor and told his parents that he would take care of them. In Mexico it is customary for doctors to pay back the cost of their training by working for the government for one year so Chalio was sent to San Luis Pedro, where, Quintanilla says, “There was no school, there was no water…we had to get it from the river, there was no electricity, there were no roads.” Since she could not go to school there, her grandfather had taught her how to read, write, and do basic arithmetic. Quintanilla helped her uncle by being his “nurse.” She practiced giving injections on an orange and cleaned his medical instruments.

The family moved to Matamoros where her uncle opened a doctor’s office. Soon after, her grandfather began to go blind, so the family moved to Brownsville, Texas, where they hoped to find doctors who could help him. In Brownsville, Quintanilla’s grandmother took her to enroll in school where she was given an IQ test. She recalls, “When I looked at the paper, I could tell that it was some kind of a test. But it was not like any test I had ever seen. There were many shapes—squares and circles and triangles. There were sentences with words missing in the middle. There were questions with numbers. And I couldn’t read a single word of it. Why not? The test was in English. I spoke only Spanish. I did the best I could. I figured out some of the math problems. I guessed at the meaning of some words. But I left most of the answers blank. I turned the paper in, feeling very confused. What kind of test was this? How was I supposed to understand?”

As one can imagine she scored very poorly, and the school labeled her as incapable of succeeding in the classroom. She adds, “You know the sad thing is that I believed it. The sad thing is not that the system decided that I was retarded, it’s that I believed it.” The school put her, a twelve-year-old, in the first grade. She did not spend her classroom time learning, however; instead, the teacher used her as an assistant, taking children to the bathroom, putting up posters, and cutting pieces of paper.

Quintanilla went on defy the odds and lead the Cross Cultural Communicaiton program creating understanding between Houston’s Hispanic community and police,

One day as Quintanilla waited for the teacher to bring the children back from recess, she heard a man’s voice say, “Donde esta la oficina del principal?” (“Where is the principal’s office?”) She felt so happy to hear someone speaking to her in her native language that she answered his question and began talking to him in Spanish. Just at that moment the teacher grabbed Quintanilla’s arm and took her to the principal’s office. “They both yelled at me a lot in English. I didn’t understand anything they were telling me but I was seeing their body language.” She felt so humiliated that she did not want to go back to school and cried until she convinced her grandfather to let her quit school. Thus, Quintanilla became a first grade drop-out at the age of thirteen.

To read the full article, click here.

Watch author Adriana Castro’s video on Dr.Quintanilla

[youtube]https://youtu.be/Plkv3Gxnc5I[/youtube]

Follow

Follow