By Marie-Theresa Hernández

In 2022, when University of Houston photography students from my World Cultures and Anthropology class excitedly entered downtown Houston to begin their photographic journey, they did not think so much of the past. At first, they were fascinated by the ultramodern construction of Houston’s first post-modern buildings, Pennzoil Place, built in 1975, and the TC Energy Center, built in 1983 as the Republic Bank Center. Yet, eventually, they found themselves at Market Square in the oldest commercial building still in use, La Carafe. Then they moved on to the Julia Ideson Building of the Houston Public Library and marveled at the reproduction Venus de Milo statue on the second floor. The following week they spent one long afternoon in Sam Houston Park, which was established in 1900 as the city’s second park, after Emancipation Park in Third Ward founded in 1872.

In our conversations, the students often talked of downtown’s corporate life, which differed significantly from theirs as students. While they took many abstract photographs of the newer buildings, they became almost obsessed with photographing the few traces of the past that they could find. They wondered why Houston did not save more of its old buildings. Why is there such a need to destroy the past and construct skyscrapers with so much glass?

The answer probably lies in Houston’s drive for survival and success. It was a dangerous place in its early years, known for its often-violent frontier culture and frequent yellow fever epidemics. Nevertheless, people held on and built a stable economy based on cotton. Once oil was discovered at Spindletop, near Beaumont, in 1901, Houston took the lead. The money flowed to Houston like water. Civic leaders worked to clean up downtown, and many working families moved closer to the industrial centers. Throughout the twentieth century, developers constructed new buildings, but downtown only had so much room, which often meant the old buildings had to go to make space for the shiny new ones. Oil and natural gas kept Houston’s economy vibrant, and this wealth produced tall glass skyscrapers surging past economic downturns.

It has been said that Houston would never have become a major city without air-conditioning. Yet it was bustling by the early twentieth century even when temperatures reached a drenching 100 degrees. Businessman Jesse H. Jones commissioned the thirty-seven-story Gulf Oil Corporation Building in 1927. Its construction was a testament to the future promise of Houston. The plans did not include air conditioning, but that did not detract from the building’s success. The only thing that slowed the progress of Houston was the Depression, which came months after the building’s completion. It has only been a century since Houston realized its possibilities as a place of wealth and power. Walking the downtown thoroughfares, my students wondered if the city would rather forget its past and only think about its future.

To read the full article and view the photo essay, click here to read the pdf or on Buy Magazines above to purchase a print copy or subscribe.

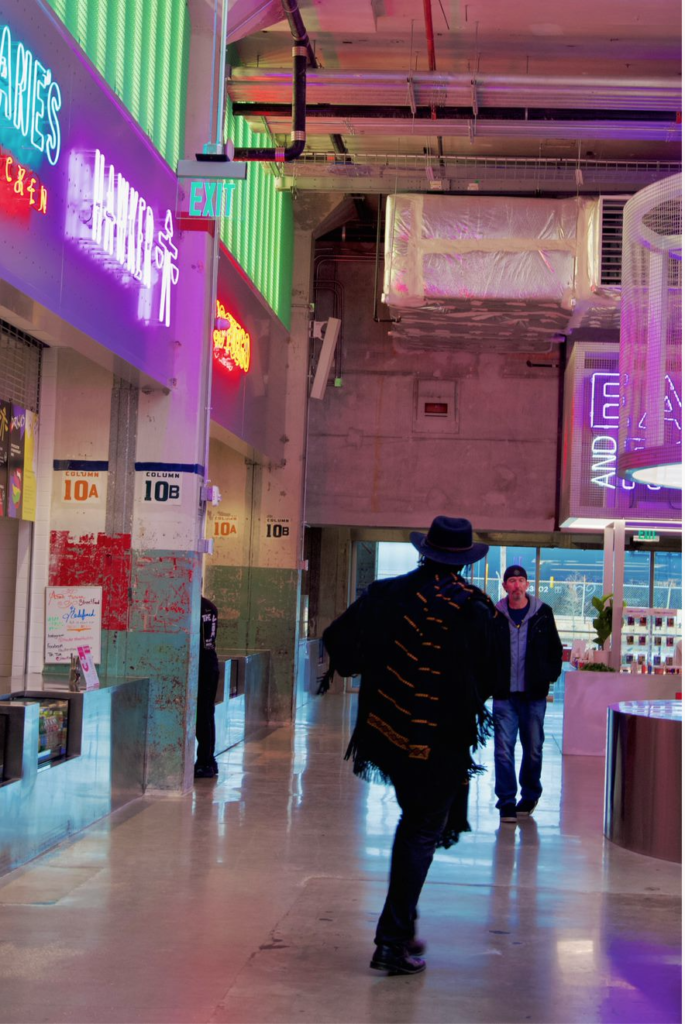

Check out more photos below that could not be featured in the magazine due to spatial limitations.

To read the full article, click on Buy Magazines to purchase a print copy or subscribe.

Follow

Follow