By Karla Rodriguez

Guadalupe was expecting her fourth child in five months’ time in October 1938. Her eyes once sparkled with joy over her children, but now they were filled with fear and grief for her beloved husband John, who had died. She worried about how she would take care of their three young children let alone a fourth. Guadalupe fell ill, perhaps from heartache, or maybe something else was wrong. But how could she afford to go to the doctor when she lacked money for food and rent? Frightened with nowhere else to turn, she arrived at the Mexican Clinic to ask for aid. Her three children trailed behind her, afraid and clinging to her skirt.

A caring doctor and attentive nurse examined Guadalupe and her children, while the women volunteers gave her hope and encouragement. She learned a great deal during her clinic visit, which eased some of her fears. Soon her health improved, and her children were more fit than they had ever been because the clinic offered her guidance on how to care for them. In an article featuring Guadalupe’s journey, the Houston Chronicle reported, “She will have a fine baby that will grow into a healthy child because the clinic will take care of the baby too.”

Before the Clinic

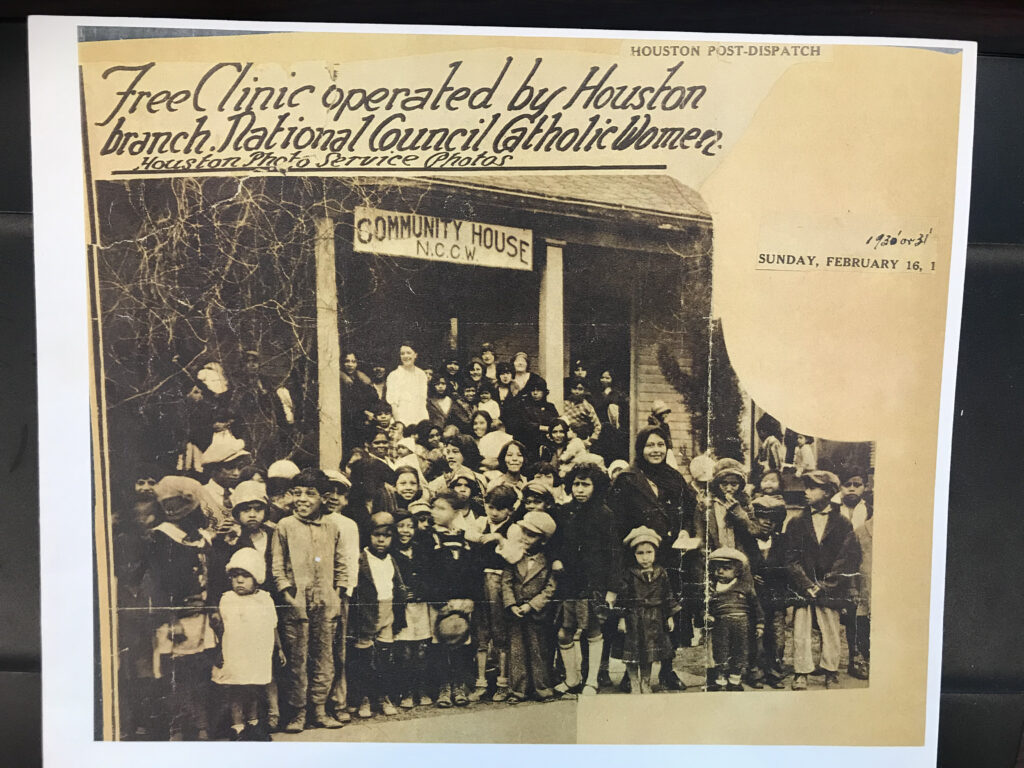

In the early twentieth century, Mexican immigrants, many fleeing revolution in their homeland, came to Houston seeking better opportunities. After World War I, however, it became more challenging for Mexicans to find employment as returning Anglo veterans displaced them, and labor unions accused the Mexicans of taking jobs from Americans. Falling into poverty, many Mexican American residents barely earned enough to survive. They represented one of the city’s most impoverished ethnic groups, living in substandard housing that lacked basics like running water, which led to rapidly deteriorating health. Most notably, pneumonia and tuberculosis brought the Mexican community’s life expectancy down lower than that of the general public.

Malnourishment and disease from their impoverished conditions led to high infant mortality, as did mothers’ lack of knowledge about childcare. According to a 1922 health report published in the Houston Chronicle, 658 children in Texas died in June alone. Of those, 58 were Mexican children under one month of age and 195 were Mexicans between one and twelve months old. Even though Mexican parents compared favorably to other ethnic groups in their care prior to a child’s birth, the report indicated a, “lack of proper hygiene result[ed] in intestinal derangement, malnutrition and enteritis [as] the principal causes of death.”

To read the full article, click here or on Buy Magazines to purchase a print copy or subscribe

https://charityguildshop.org/

Follow

Follow