By Port of Houston Authority

After 100 Houstonians promised the Southern Steamship Line that they would each pay $1,000 if the company incurred losses in offering regular service to the Port of Houston, the company declined the bond and sent the first of many ships, the Satilla, loaded with seventy-five carloads of merchandise.

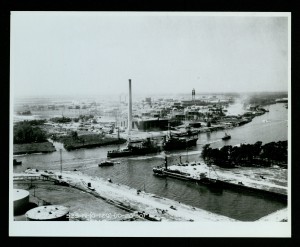

Fifty-two miles long and recognized as a public works engineering marvel, the Houston Ship Channel gave birth to the nation’s busiest port, its leading export port, its leading break bulk port, and its largest petrochemical complex. Indeed, the town that built a port that built a city sums up the Houston Ship Channel’s first century.

Luring customers to a new deep-water port in Houston proved to be difficult, especially during World War I. A few ships ventured up the channel in 1915, but many ships’ captains were skeptical about the channel’s promised depth and were unwilling to risk larger vessels in unproven waters. Also, the first public wharves were not completed until a year after the dredging finished.

Houston’s leaders had worked so long and hard to convince Congress to fund the dredging of a deep-water port that they gave little thought beyond that accomplishment. Marketing the new facilities to potential customers proved more difficult than Houstonians imagined.

The cruiser USS Houston made her way up the Houston Ship Channel in 1930 to the delight of Houstonians. Approximately 250,000 people visited the ship during her week-long stay. Photo courtesy of the US Houston (CA-30) Digital Library, Special Collections, M. D. Anderson Library, University of Houston.

Civic leadership knew that regular service by a steamship line was essential to inducing other shippers to stop at the port. Houston succeeded by using the same kind of ingenuity that convinced Congress to fund the dredging. When the Southern Steamship Company, a subsidiary of the Atlantic, Gulf and West Indies Lines, remained indifferent to the Port of Houston’s ovations in May 1915, Houstonians made the company an offer it could not refuse: a bond signed by 100 Houstonians promising to pay $1,000 each if the line incurred any losses providing regular service to the Port of Houston.

Follow

Follow