Letter from the Editor: Reflections on Love

Does anyone ever really forget their first love? Whether the relationship lasted a lifetime or ended too soon, it seems few people forget. In fact, the internet has an endless number of opinions and statistics on first loves.

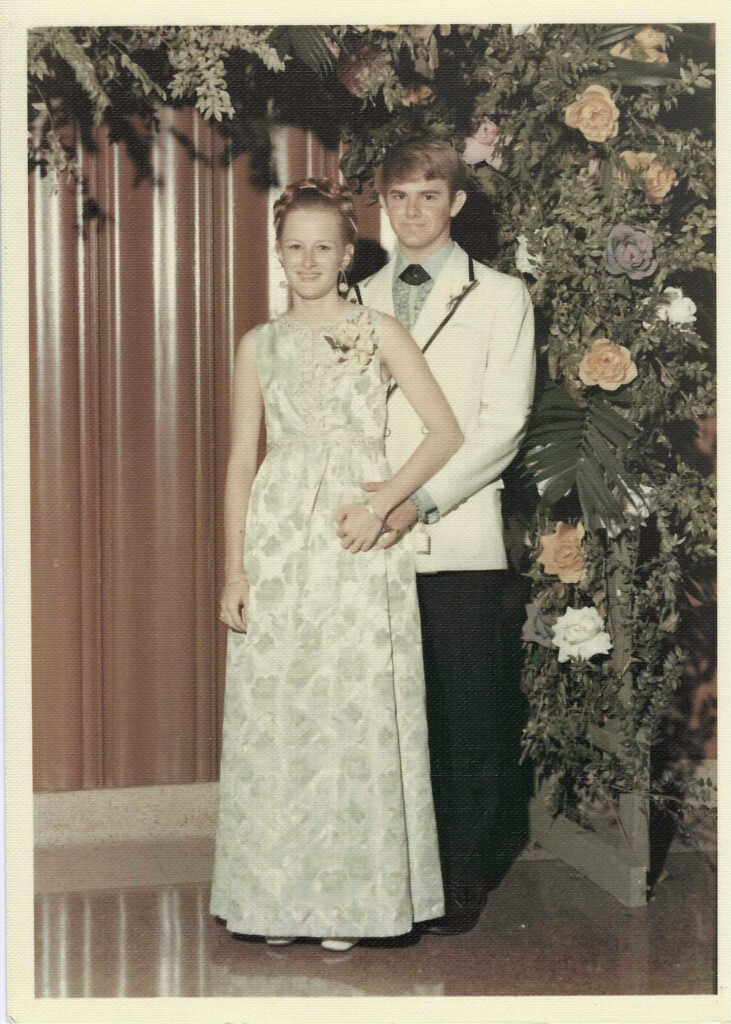

My first love was a gay man. I didn’t know that when John (later Jon) and I were in high school in the sixties, and he certainly never revealed it to anyone. Our one common bond was dancing. We practiced in my family room before every school dance, synchronizing all our steps, especially for our proms. We broke up twice, for a short time after he graduated in 1969 and again, for good, when I left for TCU the following year. Jon married briefly before coming out as a gay man – a piece of information whispered to me by an older woman who was his neighbor.

When I learned about the Texas Obituary Project in our article on Houston ARCH (Houston Area Rainbow Collective History) in spring of 2019, I immediately looked up Jon Holz, and there he was. All I could think was how much he would have loved that picture of himself in a fur coat, and how he died of AIDS far too young at forty. Then I looked up James Harvey, the son of a dear friend who also died of AIDS at twenty-six. He was there, too, smiling from the page. His mother could not find anyone to help her care for him or even come into her house because they feared catching the disease. I was grateful to find Jon, James, and 7,200 others are being remembered in this way.

Attitudes toward acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community have followed a trajectory similar to other marginalized groups. Editor emeritus Joe Pratt and I frequently talked about racial attitudes and how people in our generation evolved in our thinking as we moved out of our parents’ homes and developed meaningful relationships with people who were different from us, including Blacks, Latinos, Asians, people with disabilities, and LGBTQ+ folks. They were our college classmates, professors, mentors, coworkers, bosses, teammates, and people who became close friends.

After first learning about the Stonewall uprising three years after the fact while in college, I understood the LGBTQ+ civil rights movement sought the same rights as the movements for Blacks, women, and Chicanos – and people in all those groups shared identities. But the LGBTQ+ community seemed more in the shadows, and bashing them, even murdering them, did not draw the same outrage by society. In the last fifty-two years, hard fought legal battles have protected some rights for the LGBTQ+ community, but the fight to permanently protect their equality continues.

In the 2020 Kinder Houston Area Survey, Stephen Klineberg reports, “The national shift in attitudes toward gay rights has been one of the most striking phenomena in the history of public opinion research, and it is powerfully manifested in Houston as well.” From 2011 to 2019, the number of people who agreed “homosexual marriages should be given the same legal status as heterosexual marriages” grew from 45 to 63 percent. Similarly, from 2010 to 2020, those who favored “homosexuals being legally permitted to adopt children” rose from 49 to 62 percent. This acknowledgment of the legitimacy of LGBTQ+ families is likely due in part to Houstonians’ acceptance of diversity, but another key reason might be that from 2004 to 2019 the number of people indicating they had “a close personal friend who is gay or lesbian” increased from 41 to 60 percent. Historically people have become more accepting of folks they consider different when they have the chance to get to know them and discover they are really are not so different after all. Both groups frequently share the same goals in life, and they love their partners, families, and friends just like everyone else.

This magazine explores the prescriptions and proscriptions society has placed on love for members of the LGBTQ+ community. It looks at the meaning of love in committed relationships and how the only difference is the heartache, abuse, and hate inflicted by those from the outside against LGBTQ+ people. The article on Phyllis and Trish Frye takes us on a transformative journey and shows the power of being true to one’s authentic self, and the power of love, even when it is hard. The pieces on the Gulf Coast Archive and Museum of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender History (GCAM) and Judy Reeves, the Dr. Charles Law Community Archive, and the Dianas demonstrate the importance of preserving the history of the LGBTQ+ community to learn about their contributions and move toward greater inclusiveness. The story about Deb Murphy shines a light on the challenges of coming out as well as the triumphs that come from mentoring LGBTQ+ youth so that they can love and thrive in hard times.

Today, I have been happily married to Tom, my true love, without fear of repercussions for over forty years. My hope is that everyone can find their own love, whether it be with another person or in accepting their true self, without judgement or attacks from those who choose hate over love.

The Texas Obituary Project keeps a record of Houstonians and Texans who have died of AIDS. The project enables us to remember people who might otherwise have been forgotten or who may have been intentionally erased from public memory by those who did not want their identities revealed as having been gay or taken by AIDS.

Follow

Follow